We are an NSF-funded collaboration among historians, scientists, hydrologists, and statisticians.

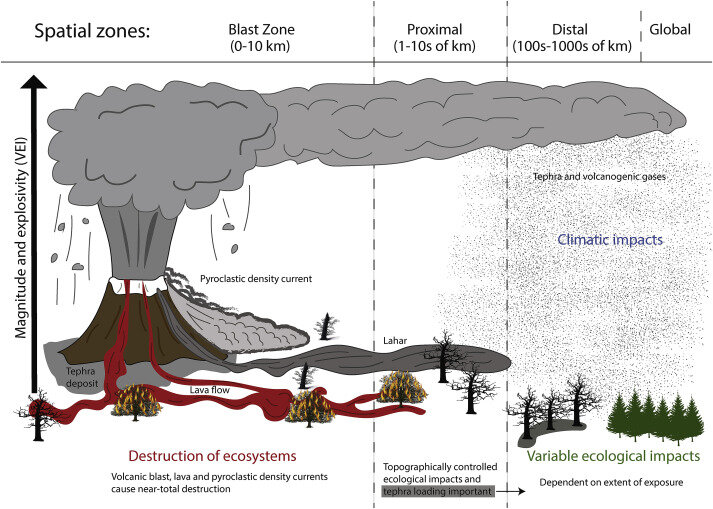

This project examines the link between explosive volcanic eruptions and the annual Nile river summer flooding in antiquity. It seeks to understand the coupling between the hydrological cycle and human society in Egypt during the Hellenistic era.

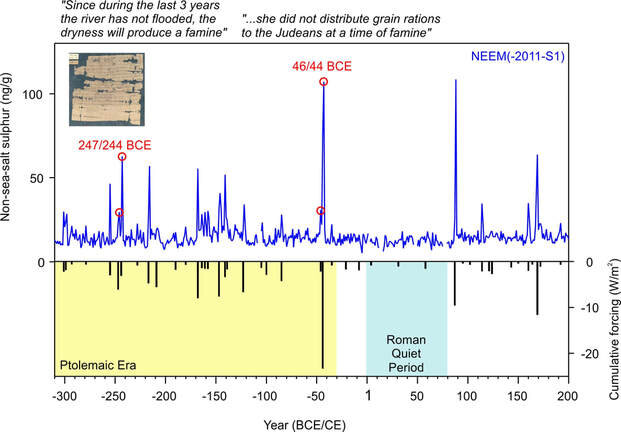

Extreme climate after massive eruption of Alaska’s Okmok volcano in 43 BCE and effects on the late Roman Republic and Ptolemaic Kingdom

Joe Manning and Francis Ludlow are co-authors on a new research paper about the environmental and societal impacts of the 43 BCE eruption of Alaska’s Okmok volcano. Using tephra deposits in six Arctic ice cores, this team of researchers identified Okmok as the site of one of the largest volcanic eruptions in the last 2,500 years. Historical documentation from the years following — a period of political upheaval witnessing the fall of the Roman Republic and Ptolemaic Kingdom and the rise of the Roman Empire — indicates unusually inclement weather, famine, and disease in the Mediterranean region, likely a result of the large volcanic eruption.

Johann Georg Platzer’s 18th-century depiction of the Battle of Actium in 31 B.C. The battle is seen as marking the end of the Roman Republic. Credit V&A Images, Via Alamy.

The 2008 eruption of Okmok. Credit Neal/Alaska Volcano Observatory/United States Geological Survey.

Ice core analysis for the fallout of the 43 B.C.E. Okmok eruption. Credit Joseph R. McConnell.

April 2020

CLIMATE CHANGES IN THE ANCIENT WORLD:

VOLCANOES, REBELLIONS, AND LESSONS FROM THE DISTANT PASS

An episode on the podcast Climate History, featuring an interview with PI Joe Manning.

About

Learn more about our project goals, current research, and future work.

Contact Us

Follow us on Twitter @NileHistory or reach out to us by email. We’d love to hear from you.

We are well into our second year of our four year grant from the US National Science Foundation (Award # 1824770, https://nsf.gov/awardsearch/showAward?AWD_ID=1824770).

Time really does fly when you are having fun! For the Yale team, the bulk of our time has been dedicated to two agendas: (1) tracking down all relevant climate proxy records that we think may be of help in our understanding of Nile river flooding anomalies in the last four centuries BCE, and (2) coding historical information derived from papyri and inscriptions, primarily, that help us understand Nile flood conditions. Here we follow the lead of the great work of Danielle Bonneau, Le Fisc et le Nil (1971), but we have added many new texts, including Egyptian language sources, and several other data about the source. In addition to attempting to code the quality of the flood year by year, we add Geocoding, an uncertainty index, and pertinent information from each source.